THE MANY FACES OF FISHERTON

Many of Salisbury’s most important buildings and institutions – now or in the past – are not really Salisbury at all, but in Fisherton. Hospitals, railway stations, prisons, theatres, not to mention car parks and the main industrial estate, gasworks and malthouses, businesses of various kinds, inns and housing – all things vital to Salisbury’s well being – are located in Fisherton.

Fisherton’s full name is Fisherton Anger (pronounced like Ranger), and it is Salisbury’s older neighbour. It was a village at least 150 years before the city of New Sarum, that precocious neighbour across the river, was first laid out in the 13th century. The original settlement probably lay along what is now Mill Road, between the station and the river.

Here was its church, and you can still see the graveyard (now The Secret Garden), although the building was demolished more than a century ago. Behind the church were fields (Churchfields) and against the river stood a mill. The rivers were harvested for fish (hence the name of the village), and crops grew in fields alongside the Wilton Road.

It is stated that St. Clement was probably the forth Bishop of Rome, and that he was a disciple of St. Peter, the first Bishop of Rome. On February 15th, 1852, divine service was performed in the old Fisherton Church for the last time and on February 3rd, 1853, the new church of St. Paul’s was consecrated.

When Salisbury arrived next door the people of Fisherton sensed a good thing. They found themselves in between the two most important towns in South Wiltshire, Salisbury and Wilton, and the road connecting them was ripe for commercial development. Rapidly the villagers’ attention, and much of the village itself, moved to Fisherton Street, where they could join in Salisbury’s success. The Street became lined with houses and shops, important inns and even a friary.

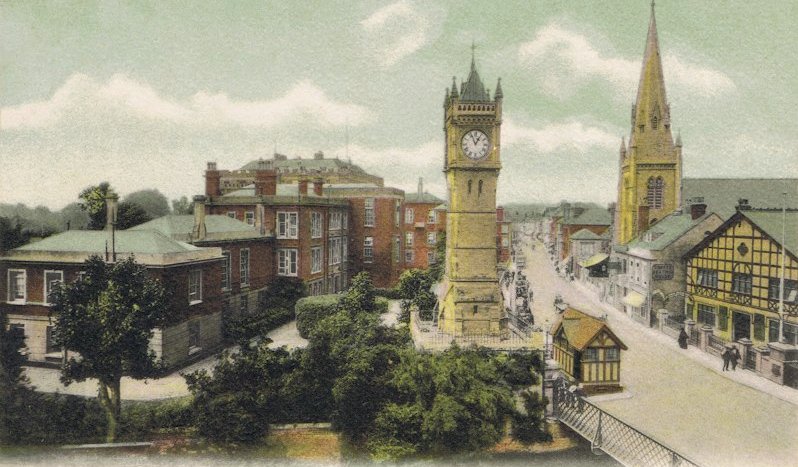

Later on, in 1578, the county jail for Wiltshire was built next to Fisherton Bridge and later still, in 1771, the Infirmary opened nearby. The only remaining part of the old Fisherton jail is now part of the Fisherton clock tower which a Salisbury doctor named John Roberts had built in 1892 as a memorial to his wife, Arabella.

As mentioned, the Infirmary opened in 1771 and lasted until 1991-1992, when all medical services began to transfer to the Odstock hospital site, to the newly named Salisbury District Hospital.

This Old Manor psychiatric hospital was also in Fisherton and was originally known as Fisherton House asylum – it was also known as Fisherton madhouse in some quarters.

Progress of a different sort turned all Salisbury eyes on Fisherton in 1856, with the building of railway stations – the first of which was the GWR designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Now Fisherton Street linked Salisbury to the outside world.

On 2 May 1859, the LSWR opened a station right next to the first railway station and this is our current railway station.

Before the railways, Fisherton’s businesses were a small proportion of the city’s. In 1848, of some 350 businesses in Salisbury, 50 were located in Fisherton, and of these – alongside 5 general shopkeepers, 7 public houses and a beer retailer – only 7 lent any kind of industrial character to Salisbury’s western suburb. These were 2 blacksmiths, a coach-smith, a wheelwright, a wire-maker, the gas works and a brick-maker.

A similar situation prevailed in 1907. Then some 900 businesses were listed in Salisbury, of which 209 – a higher proportion than 60 years earlier – were based in Fisherton. Of these no more than 30 were engaged in manufacture – or any kind of engineering – but it is the character of the largest of these enterprises which gave Fisherton its distinct atmosphere.

These firms comprised firstly of the maltings built in the last quarter of the 19th century on land to the north of Fisherton Street by Messrs Williams brothers who had moved to Fisherton around 1867. Five great square buildings and a sixth, L-shaped by the River Avon, most of them over 100 feet square, covering an area of about one and a quarters acres. Between them, from the downside of the station to the city’s Market House, ran the country’s shortest standard-gauge railway. From these premises Williams produced ‘pale, brown, patent, crystal and amber malts.

Then there were the 3 utilities, of which the largest employer was the gasworks. This was enormously labour intensive, more akin to a chemical works since, as well as producing gas, and its major by-product coke, other by-products included tar and agricultural fertilisers. From every ton of coal, about 13,000 cubic feet of gas was produced, but every ton of coal had to be brought by horse-drawn cart a quarter of a mile up the Devizes Road and into Gas Lane to the coal store in the works. The gas works had arrived in 1833, occupying a site of just over half an acre to the north west of Devises Road. As the business developed, more land was purchased in 1868 and 1878 – about 3 acres in all.

Another major manufacturer in Fisherton in the second half of the 19th century had been Robert Harding, proprietor of the brick, lime and whiting works to the south west of Devises Road. His works had provided much of the raw materials for Fisherton’s rapid housing up to 1900, and occupied about six acres.

By 1907 the firm had ceased trading, and bricks for Salisbury’s continued expansion came from brickworks outside the city. The site of Harding’s brickworks was then developed for housing and industrial use and the centrepiece of the scheme was a milk processing factory which opened in April 1908. The milk company claimed to supply milk: “from the best farms in the district, to households in sealed bottles, and also to royalty.” Proud claims indeed although a less enthusiastic response came from some Fishonians who didn’t take kindly to the factory siren which would sound at 6.30am and throughout the day!

The largest single employment sector was that of the railway and although there was no engineering or manufacture as there was in Swindon, Ashford or Eastleigh, there was an enormous amount of passenger rail traffic to, from and through Fisherton.

Taking into account rail freight traffic as well – the presence of Milford Station as a depot notwithstanding – one can readily appreciate why there were so many railway workers in Fisherton’s more recent housing developments. One telling example of the station’s increasing busyness was demolition of 14 cottages known as Railway Terrace to make way for the Post Office Sorting Office.

By the late 19th century the area around St. Paul’s was know as the ‘Railway Town’ and had its own shops, such as Saunders in York Road and Slades in Meadow Road – both grocers and provision dealers, and by 1907 a branch of the Co-op on the corner of York Road. By 1908 there was also a public house, The Duke of York, ably managed by Miss Beatrice Newman.

1908 was also the year of Salisbury’s most infamous murder – that of a 12 year old boy named Teddy Haskell. Teddy had already suffered the trauma of losing a leg through TB and when he was found in bed with his throat cut, his mother was duly arrested for the crime. However, after two court cases she was found not guilty through lack of evidence. The case made national headlines throughout England – not least because the case was put into the hands of chief inspector Walter Dew from London. Dew had works on the Jack the Ripper investigation and in 1910, became a Scotland Yard superstar when he arrested the notorious Dr. Crippen. So in between Jtr and Dr. Crippen, Inspector Dew was in Fisherton! Even though Flora, the boy’s mother, was found not guilty, she could never return to Fisherton. She moved to London to live with her brother where she died of TB in1920.

The county Gaol obviously played a large part in the history of Fisherton and warrants a presentation of its own! It was closed in 1870 and all but the central administration block and chapel were demolished in 1875. The central block became the headquarters of the second army corps, later the Southern Command.

Whilst the gaol had been the site of executions earlier in the century, the city gallows for public executions in earlier times had been at the junction of Devises and Wilton Roads, right opposite the site of the prison, which was known locally as ‘Gaol Ground Area.’

When the old gaol became available for purchase in 1875, Thomas Scamell joined forces with Thomas Leach, a grocer at Oatmeal Row, and Stephen Hill, a solicitor at Endless Street, to purchase it for £6, 305 for residential development. Eventually over 230 were built on the Gaol Ground and most famously, Thomas Scamell drained the water meadows and built a 600 metre road across them via a bridge to link Castle Road with the western station end of Fisherton Street. Scamell was able to charge a toll of 1d to pedestrians for crossing the bridge and was not a popular man! However, it was later recognised that the work offered a great advantage to the neighbourhood.

A strange episode is the death of Thomas Scamell. He died, tragically and inexplicably on the 20th May 1903 on the railway line not far from his home in York Road. The family insisted that he had no worries whatever on his mind, but the death was by decapitation, which implies a degree of deliberation – was it foul play?

As mentioned, the largest employment sector was that of the railway. Of the 277 main householders in the Fisherton Railway Town in 1897, 88 (32%) were railway employees – 30 were engine drivers, 16 were firemen, 10 were guards and 10 were porters. There was a coal trimmer, a carriage examiner, a platelayer, a parcel clerk, an inspector and a Railway Clearing House number taker. The 27 houses of Clifton Terrace had a striking concentration of railwaymen comprising 7 engine drivers, 2 guards, 2 firemen, 2 signalmen, a porter and a ticket collector.

So when calamity struck on July 1st 1906 the people of Fisherton were devastated. In fact, the news of the Salisbury Railway Disaster made international news because of the 28 people who died, most were Americans.

It has never been established why the train travelling from Plymouth to London Waterloo failed to navigate a very sharp curve at the eastern end of Salisbury railway station but the news spread through Salisbury like wildfire – at one point it seemed like the whole of Salisbury had descended on the station to observe the spectacle. There is a memorial plaque in Salisbury Cathedral.

The first recorded Fisherton trader was William Francis. When he died in 1286 he had 6 shops, 3 other premises, a few acres of farmland and his own residence – all in Fisherton. The shops, no doubt, occupied Fisherton Street, and were soon joined by others, and especially by inns. During the 16th and 17th centuries, as the number of travellers passing through Salisbury increased, Fisherton Street was lined with inns, of which The Sun, on the North side of the river, was the most famous, and which had its own theatre.

In fact, Fisherton is well known as Salisbury’s culture quarter and was home to cinemas and theatres.

What made Fisherton attractive to innkeepers and other traders was partly its independence. Until 1835, when the city boundaries were extended, Salisbury stopped at the River Avon. The city authorities had no control over Fisherton, whose businessmen and women relished their independence from civic control. Although this was lost in 1835, the silver lining came 20 years later. The railway stations opened, and nearly everyone entering and leaving Salisbury now had to walk along Fisherton Street. A writer in 1910 spoke of the crowds on market days ‘pouring down Fisherton Street in continuous procession, all hurrying towards the market.

Shops and other businesses specialising in wares of all kinds sprang up, and gave the street the sturdy Victorian character – much of its architecture still remains. By 1875 there were butchers and drapers, grocers and bakers, jewellers, blacksmiths, tobacconists, tailors and fishmongers. You could buy underwear, rope, coal or a headstone, and you could stop off at pubs and refreshment rooms. Behind the street were the premises of builders and timber merchants, maltsters and market gardeners.

The flourishing of Victorian Fisherton Street reflected the growth of Salisbury itself, and it was rapidly spreading with housing across farmland which had once been the farmland of Fisherton Village.

It was very unfortunate that the area of Fisherton was renowned for its flooding and there are many photographs of Fisherton Street under water. The newspapers mention the floods of 1883 and 1915 which really affected the Fisherton area.

Fisherton certainly has a fascinating history which is probably why I decided to make it my home!

Frogg Moody